Hamiltonian Systems: The Mathematics of Conservation

Most of us first learn mechanics through Newton’s laws.

Forces cause accelerations. Motion is explained by pushes and pulls.

This perspective works remarkably well—but it isn’t the only way to understand motion.

There is another framework, one that doesn’t begin with forces at all. Instead, it places energy, symmetry, and geometry at the center of the story. This is Hamiltonian mechanics, and it reveals why certain motions persist forever while others decay, stabilize, or self-regulate.

A simple question motivates everything that follows:

Why does the Earth keep orbiting the Sun without slowing down?

The answer is not “because gravity pulls it just right.”

The deeper answer is that the Earth–Sun system is Hamiltonian.

Energy as the Main Character

In Hamiltonian mechanics, energy is not just a conserved quantity—it is the object that generates motion.

For many familiar systems, total energy splits into two parts:

- Kinetic energy, associated with motion

- Potential energy, associated with position

If no energy is added or removed—no friction, no drag, no dissipation—then the total energy remains constant.

This single fact already imposes strong restrictions. A system with fixed total energy cannot wander freely through all possible states. Instead, its motion is constrained to surfaces of constant energy.

Energy Landscape

The particle moves only where E ≥ V(x). Turning points occur where E = V(x).

Phase Space: Where Motion Really Lives

Rather than plotting position as a function of time, Hamiltonian mechanics describes motion in phase space.

For a one-dimensional system:

- Horizontal axis: position ( q )

- Vertical axis: momentum ( p )

A single point ( (q, p) ) represents the entire state of the system at an instant. As time evolves, this point traces a curve through phase space.

For conservative systems, trajectories do not spiral inward or outward. They form closed curves (for periodic motion) or extended structures—but they never collapse or intersect.

The geometry of these trajectories is the dynamics.

Harmonic Oscillator Phase Portrait

Each closed curve represents a constant energy level. The orange point traces its orbit with period T = 2π/ω ≈ 6.28s. All trajectories are ellipses centered at the origin—a hallmark of the harmonic oscillator.

Enter the Hamiltonian

At the center of Hamiltonian mechanics lies a single function: the Hamiltonian.

It is not an equation of motion, nor a force law. It is a scalar function that encodes the total energy of the system in terms of position and momentum:

For many classical systems, the kinetic energy depends only on momentum,

while the potential energy depends only on position.

Once the Hamiltonian is known, the equations of motion follow immediately:

These are Hamilton’s equations. They describe how the system moves through phase space as time evolves.

Hamilton’s Equations “Vector Field”

The full vector field shows how both position and momentum evolve simultaneously. The flow rotates clockwise around the origin—a signature of conservative Hamiltonian systems. Click anywhere to place the particle.

Newton vs. Hamilton: Two Views of the Same Physics

Hamiltonian mechanics does not replace Newtonian mechanics—it reframes it.

| Newtonian Mechanics | Hamiltonian Mechanics |

|---|---|

| Variables: position (x), velocity (v) | Variables: position (q), momentum (p) |

| Core equation: (F = ma) | Hamilton’s equations |

| Motion driven by forces | Motion generated by energy |

| Local, force-by-force reasoning | Global, structural reasoning |

Both frameworks describe the same physical reality, but the Hamiltonian viewpoint exposes structure that is invisible in the force-based picture—especially conservation laws and long-term behavior.

A Worked Example: The Harmonic Oscillator

Consider a mass attached to a spring. Its Hamiltonian is

Applying Hamilton’s equations:

Taking a time derivative of the first equation and substituting the second gives

which is exactly Newton’s second law for a spring.

The physics is unchanged—but the logic is different. Motion emerges from energy gradients rather than forces.

What Makes a System Conservative?

A Hamiltonian system has several defining properties:

- Energy is conserved: ( H(q(t), p(t)) = C )

- No dissipation: no friction, no drag, no energy loss

- Time reversibility: reversing time produces a valid trajectory

- Phase space volume is preserved

Conservative vs Dissipative (Side-by-Side)

Left: energy stays constant, so trajectories don’t spiral. Right: damping removes energy, so trajectories spiral into an attractor.

That last property leads to one of the deepest results in the theory.

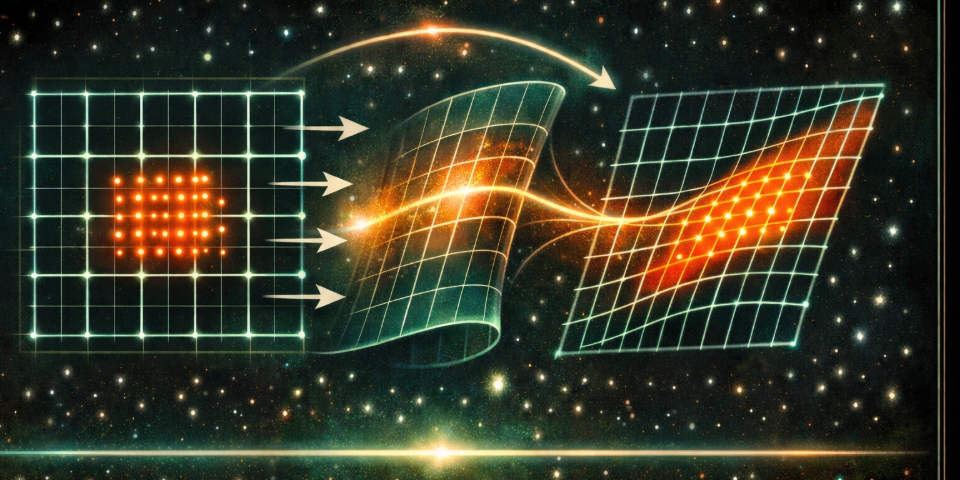

Liouville’s Theorem and Phase Space Structure

Hamiltonian flows behave like an incompressible fluid in phase space.

Liouville’s theorem states that any region of phase space evolves without changing its volume. It may stretch, shear, and fold—but it never shrinks or expands.

This has powerful consequences:

- Trajectories cannot converge to attractors

- Stable fixed points and limit cycles cannot exist

- Long-term dissipation is impossible without external effects

This is why purely Hamiltonian systems cannot “settle down.” They preserve structure forever.

Liouville “Blob” (Area-Preserving Flow)

Watch as the blob stretches, shears, and rotates—but its area remains constant. This is Liouville's theorem: Hamiltonian flow preserves phase space volume. The color indicates conservation quality (green = excellent, yellow = good, red = numerical drift). Any deviation from ratio=1.0 is due to numerical integration error, not physics.

The Earth and the Sun

For a planet orbiting the Sun, the Hamiltonian (schematically) is

Two facts follow immediately:

- Energy conservation fixes the orbit’s size and shape

- Angular momentum conservation keeps the motion planar

Energy continuously trades between kinetic and potential forms—faster near perihelion, slower near aphelion—but the total never changes.

Space is nearly empty. With no friction to remove energy, the orbit persists.

This stability is not accidental. It is a geometric consequence of Hamiltonian structure.

Orbit Energy Exchange

Near perihelion the planet moves faster (T increases) and the potential well is deeper (|V| increases). The sum H stays constant for an ideal Kepler orbit.

Symmetry and Conservation

Conservation laws arise from symmetry:

- Time translation symmetry → energy conservation

- Rotational symmetry → angular momentum conservation

- Spatial translation symmetry → linear momentum conservation

This connection is formalized by Noether’s theorem, which shows that conservation laws are built into the structure of physical law itself.

Symmetry → Conservation Map

Symmetry is structure. Conservation is the shadow it casts on dynamics.

What Hamiltonian Systems Can—and Cannot—Do

Hamiltonian systems can exhibit:

- Periodic motion

- Quasiperiodic motion

- Chaos (as in the three-body problem)

- Rich geometric structure

But they cannot:

- Lose energy spontaneously

- Converge to stable equilibria

- Form limit cycles

- Forget their initial conditions

If a system shows damping, attraction, or self-regulation, something non-Hamiltonian is at work.

When Conservation Breaks

Real systems are never perfectly isolated.

Tidal friction, gravitational radiation, and external perturbations slowly break conservation laws. Over extremely long timescales, even planetary orbits evolve.

But these effects are tiny. On human timescales, the Earth–Sun system is effectively Hamiltonian.

Understanding where Hamiltonian mechanics applies—and where it fails—is just as important as understanding the theory itself.

Why Learn Hamiltonian Mechanics?

Hamiltonian mechanics is the gateway to:

- Quantum mechanics

- Chaos theory

- Statistical mechanics

- Symplectic geometry

- Modern dynamical systems

Conceptually, it teaches a powerful lesson:

Motion is constrained not just by forces, but by structure.

Final Thoughts

Hamiltonian systems describe a universe where energy flows between forms but never disappears. They explain why some motions persist forever, while others require continuous input and dissipation.

The Earth’s orbit is not merely stable—it is structurally protected.

To understand Hamiltonian mechanics is to learn to see motion geometrically, globally, and structurally. It is a shift in perspective that changes how dynamics looks at every scale.