The Image of Compact Sets: A Love Letter to Continuity

When I first discovered Lean, I was captivated by the idea of machine-verified mathematics. In my journey into Lean, I learned the basics of tactics and simple proofs. Now, I want to tackle something with real mathematical depth—a theorem from my point-set topology class that I took a year and a half ago.

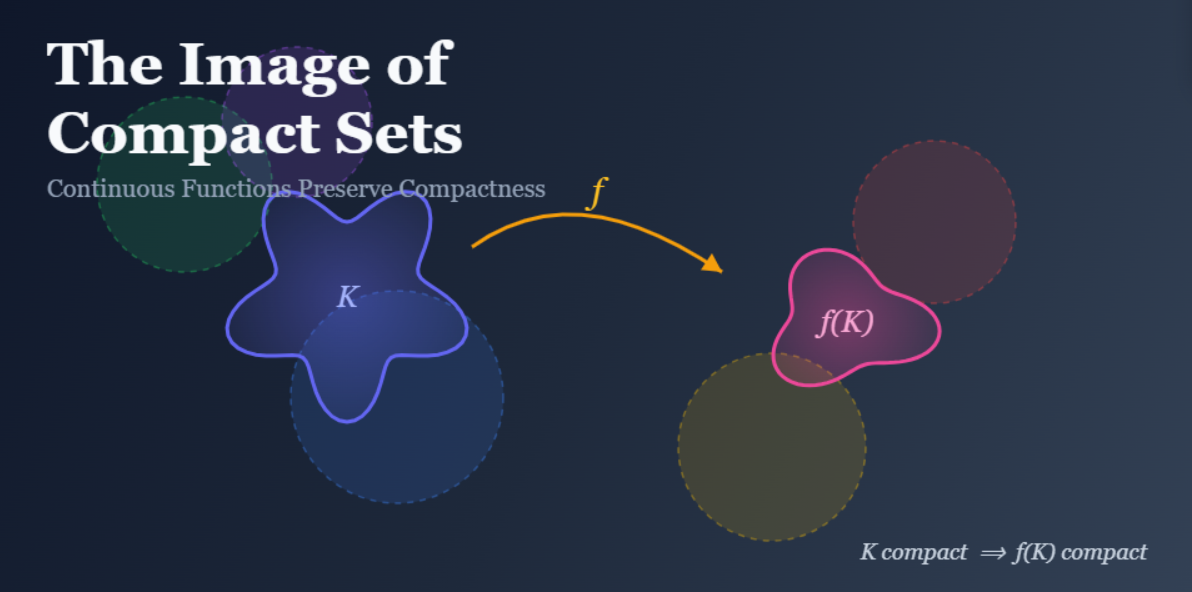

We used an inquiry-based learning approach in that class, which I loved. We built mathematics together, one definition and proof at a time, eventually assembling our collective work into a short book. One theorem that’s stayed with me is this beautiful result about how continuous functions preserve compactness. Let me share it with you, and in the next post, I’ll show you how to formalize it in Lean.

Setting the Stage: What is Compactness?

Before we dive into the main theorem, we need to understand what compactness means. The definition might seem technical at first, but it captures a surprisingly intuitive geometric idea.

Cover and Subcover: An indexing set

Open Cover: In a topological space

Compactness: Here’s the key definition. A subset

Think about what this means: no matter how you try to cover

A Warmup: Closed Subsets of Compact Sets

Before tackling our main theorem, let’s prove something useful: if

The Proof Idea: We start with an arbitrary open cover

This means

Now comes the punchline:

Therefore

The Main Event: Continuous Functions Preserve Compactness

Now we’re ready for the theorem that motivated this post:

Theorem: Let

This is remarkable! Continuity is a local property—it’s about what happens in neighborhoods around points. Compactness is a global property—it’s about covers of entire sets. Yet continuous functions bridge these worlds: they take compact sets to compact sets.

The Proof Strategy: We need to show

Taking preimages (and using the fact that

Here’s where continuity enters! Since

By compactness of

Applying

Therefore

Why This Matters

This theorem is more than just a technical result. It tells us that compactness is a topological invariant under continuous maps. If you have a compact space and you continuously deform it, the image remains compact. This is why we can prove things like: the continuous image of

The proof itself is a beautiful dance between covers in the codomain and preimages in the domain, orchestrated by the continuity of

Coming Up Next

In my next post, I’ll show you how to formalize this exact proof in Lean. We’ll see how the mathematical ideas we’ve explored translate into precise, machine-verified code. It’s a natural next step in my Lean journey—moving from basic proofs to formalizing real mathematics from my coursework.

This theorem appears in the topology book my class wrote together. Special thanks to my professor and classmates for that collaborative mathematical journey.

This post is part of my series on learning Lean. Previous posts: Discovering Lean | A Mathematician’s Journey into Lean